Data privacy: the debacle & the debate (GDPR vs PDP)

In an increasingly data driven digital economy, Big Tech companies have an eye, ear, and finger on the pulse of billions.

Depending on how deep you’ve let Amazon, Facebook, and Google sync into your life (pun intended), the data these companies have access to has reached an increasing level of detail. The digital era has molded us into great liars when it comes to signing up to online sites. While complaining about how ridiculous it seems to identify traffic lights to prove we’re not robots, we mechanically lie about reading all the Terms and Conditions. By agreeing to the T&C we may have inadvertently let the company use and sell our data for reasons we weren’t aware of.

Contextualizing the need for personal data protection

In the past few years, the headlines have been replete with worrying instances from the digital world. From large scale data breaches to controversial targeted political ad policies and inconclusive investigative hearings on privacy. The Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal of 2018 exposed how unethically sourced personal data could be used for thought manipulation. Data of about 87 million Facebook users was inappropriately harvested by the political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica, and was used for electoral advertising.

The mammoth scale and global repercussions of this scandal altered the history of the privacy debate. It revealed the imperative need to have wide-scale legal mechanisms. A system needed to be enforced to regulate what data will be collected, what it will be used for, and how permission should be sought from its owners. Organizations would have to be held accountable to such provisions through a transparent legal process. These regulations were to be designed to protect the privacy and personal data of netizens and perhaps rein in the power and influence of giant tech companies.

Introducing EU’s GDPR and India’s PDP

The European Union set precedence with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR was adopted in 2016 and enforced on 25 May 2018. It is not a mere directive, but a regulation. This implies that it is directly binding and applicable although it does allow for some flexibility to individual member nations to adjust the provisions. The GDPR is also not an Act, which means that its members have passed their own legislations based on the regulation.

In India, a regulation governing data privacy and data protection is set to be passed this year. The need stemmed from the 2017 Supreme Court judgement on the Right to Privacy. (Read our article on how the judgment impacted the digital world and the financial sector here.) A draft data protection bill was then composed by a committee headed by Justice B. N. Srikrishna. After about 2 years of contentious debate on the bill, during which it was floated for public feedback from stakeholders, it was tabled in the Indian Parliament on 11 December 2019. Currently, a joint parliamentary committee is scrutinizing the revised draft of the bill, codified as the Personal Data Protection Bill (PDP Bill). Post this, it will be debated in the Indian Parliament and finally passed.

It is yet to be determined whether the Indian PDP Bill is closer to the EU’s progressive GDPR or to China’s policy of control. Either way, it has managed to irk both Big Tech companies and privacy advocates alike. Companies with data banks aren’t happy with the cost and hassle of compliance. They deem the bill as isolationist due to its restrictive certification requirements to operate in India. Privacy advocates highlight how the exceptions in the bill can lead to State excesses of control over our data. They warn of government mission creep. Mission creep is the gradual expansion of an intervention, here, it implies the dangerous possibility of the State having access to all our data in the absence of a Privacy Law.

This blog is an exploration of how the GDPR and PDP Bill are similar, yet different in various ways.

Coming to terms with the terminology

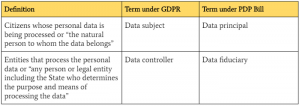

Before delving into specifics, it’s important to be acquainted with the terminology used in the legal mechanisms for data privacy. The two regulations also use different terms for the same entity:

- Data processor: Any person or legal entity including the State who processes the data. This may consist of the data controller or data fiduciary itself or a third party.

- Interestingly, the PDP Bill’s definition of personal data differs from the international definition in the GDPR.

Thematic classification of differences

The underlying principles and intent of the PDP Bill resemble the provisions enshrined in the GDPR. Aspects such as the need to have a clear purpose of processing personal data, consent requirements, personal rights, and the appointment of Data Protection Officers in organizations are closely adapted from the GDPR.

However, there are a range of differences between these two instruments of privacy. Here, the language and enforcement provisions aren’t compared, but the stance both mechanisms take on different issues.

These have been classified into the following themes:

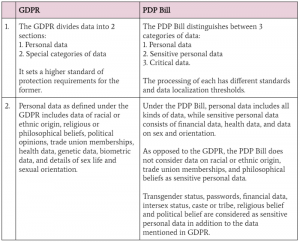

1. Classification of data

Critical data has not yet been defined by the Indian government. Although the category resembles the list of “special categories” in the GDPR, the EU’s regulation has defined what the category entails while in India the government has the power to declare any data as critical data. The GDPR does not have separate localization rules for this type of data, unlike India. This is explained ahead.

2. Data localization and cross border data flows

Data localisation requires the collection, processing, or storage of certain types of data within the borders of the nation where the data was generated, before being internationally transferred.

GDPR stance

The aim of data protection frameworks is to protect the data while safeguarding its free flow. The GDPR has no hard data localization conditions. It allows for cross-border transfer of all types of data if the country of data transfer has an adequate framework of data protection.

PDP Bill stance

On the other hand, the Indian regulation’s requirements seem to restrict data’s free flow.

- Sensitive personal data: This category of data when collected, shared or disclosed to the data fiduciary in India has to be stored only within the borders of the State. It may be transferred beyond the territory of India for processing, subject to explicit consent and conditions.

- Critical personal data: Strict data localization norms exist for this category of data. It can only be processed within the borders of India. The problem arises since this type of data has not even been defined yet.

Due to firm opposition, the 2018 draft was amended to dilute data localisation requirements (such as storing a mirror copy of all personal data in India). Yet, the GDPR’s approach to handling data is considered more pragmatic since it ensures data gets similar protection once it moves out of the jurisdiction of the regulation.

3. Right to restrict processing

The GDPR grants the data subject the right to limit the processing of their data. This means that the processing of personal data can be stalled at an intermittent stage. This can be requested on the grounds of unlawful processing, data inaccuracy etc. The PDP Bill doesn’t enshrine any such right to the data subject.

4. Right to not be subjected to automated decisions

The GDPR grants the right to not be subjected to automated decision-making, such as profiling. Profiling is the automated processing of personal data to assess certain things about an individual. This right gives the data subject the recourse of obtaining human intervention. This is when such data is solely automatically processed to make an important decision, has legal consequences or significantly affects the individual.

For example, automated processing can be used to profile potential behaviour of an individual in a faster way. It is possible that the individual will not behave in the manner the results project. In that case, if such profiling affects the legal rights of the individual, the person can legally request human intervention.

The PDP Bill does not ascertain this right. While it encourages individuals to seek remedy through courts in case of such discrimination, it does not empower an individual to decide how their data should be processed.

5. Storage limitation

The GDPR lays down specific exceptions for increasing the storage period of collected data. These exceptions include public interest, historical, scientific, and statistical reasons.

On the other hand, the PDP Bill mandates the explicit consent of the data principal to store data for a longer duration of time than is needed to satisfy the purpose for which it is collected. The GDPR does not necessitate this consent.

What does this mean for your organization?

The most contentious question is whether GDPR compliance implies PDP compliance. It is briefly addressed in this section to understand how these bills affect an organization’s compliance needs.

- Areas such as the anonymization standards differ between the PDP Bill and the GDPR.

- With no parallel of ‘critical personal data’ in the GDPR, companies will have to be careful with their processing of this classification for India.

- Unlike the GDPR, the PDP Bill also mandates the explicit consent of the data principal to store data for a longer duration of time.

Such differences and more, warrant that companies pay close attention to the compliance needs of the PDP Bill, even if they meet the requirements of the GDPR.

Other interesting follow-up questions will be explored in our next blog in the PDP Bill series.

About Signzy

Signzy is a market-leading platform redefining the speed, accuracy, and experience of how financial institutions are onboarding customers and businesses – using the digital medium. The company’s award-winning no-code GO platform delivers seamless, end-to-end, and multi-channel onboarding journeys while offering customizable workflows. In addition, it gives these players access to an aggregated marketplace of 240+ bespoke APIs that can be easily added to any workflow with simple widgets.

Signzy is enabling ten million+ end customer and business onboarding every month at a success rate of 99% while reducing the speed to market from 6 months to 3-4 weeks. It works with over 240+ FIs globally, including the 4 largest banks in India, a Top 3 acquiring Bank in the US, and has a robust global partnership with Mastercard and Microsoft. The company’s product team is based out of Bengaluru and has a strong presence in Mumbai, New York, and Dubai.

Visit www.signzy.com for more information about us.

You can reach out to our team at reachout@signzy.com

Written By:

Signzy

Written by an insightful Signzian intent on learning and sharing knowledge.